Buildings: Materials

Materials used in new construction are important, but those available to improve the energy efficiency of existing buildings might be even more important

As the first in the series, the issue on materials was supposed to be about innovation in the materials space - things like concrete, roofing, insulation. People working on those kinds of things have made huge strides recently.

I’ve seen so many examples of really innovative and interesting products like living roofs, concrete made from sustainable materials, sustainable 3D printed homes, and so on. But, as I did some research and thought about it, I realized most of those really new, innovative materials are still being developed. A few are on the market, but most aren’t yet, or if they are only in a limited way. I decided to look more closely at what is available now.

Originally, I also planned to talk about all kinds of buildings, but a few statistics changed my approach:

90% of the buildings in the United States are single family homes

80% of the buildings that will exist in 2050 are already built today (side note on sources - found this statistic everywhere - McKinsey & Company seems like the most likely original source)

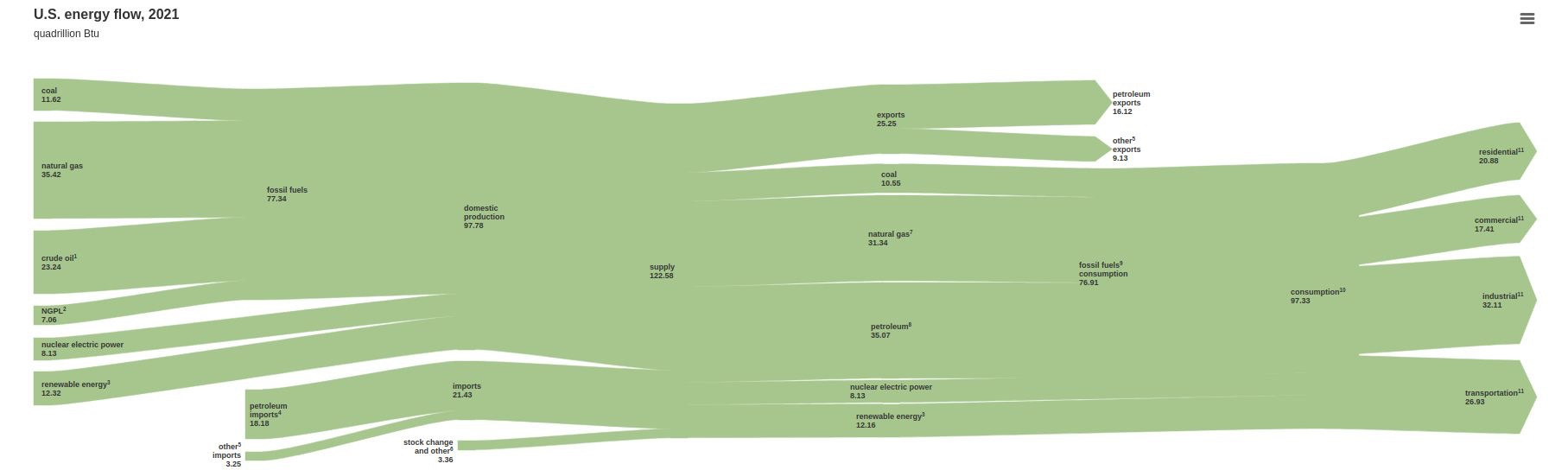

Residential and commercial building energy consumption makes up 40% of the total energy consumption in the US (remember: 90% of buildings are single family homes)

About 20% of US greenhouse gas emissions comes from homes, which is comparable to the total emissions from Brazil

32% of energy used in homes is for heating

29% is for cooling

24% is for water heating

The remaining energy usage in homes is divided between appliances (9%), lighting (4%), and other (2%)

This group of statistics made me change how I’m looking at the entire topic of “materials” because retrofitting--making existing buildings, especially homes, more energy efficient--looks to be the key to reaching net zero in the built environment. Yes, schools, offices, and apartment buildings have a role to play as well, but with the majority of buildings being single family homes, it seems most pertinent to stress the materials available for retrofitting the houses we live in.

Knowing that a sizeable percentage of carbon emissions comes from homes is another way that individual impact really does matter.

Personal Experience with Materials

We began our home-owning journey with a building that likely wouldn’t have qualified in anyone’s mind as a home. It was closer to a shell. There was no electricity or plumbing, though we did have a septic tank. It was essentially a foundation with a frame, subflooring, a roof (that leaked), and siding. No interior walls, ceilings, or fixtures. No heat, no appliances.

Making that house more livable provided many lessons in materials necessary for constructing a house, and doing the research for this newsletter revealed that in the intervening years (we’ve been in our current home for about 16 years or so now) much has changed.

For almost any project you care to name, the choice of materials, tools, and appliances has changed dramatically. Grant Gunnison, founder and CEO of Zero Homes was kind enough to take the time to discuss materials and retrofitting with me and, during our conversation we talked about the sheer number of hours of consultation with contractors necessary to improve energy efficiency in single family homes in the US. If there are 60 million homes, and each one needs 100 hours of expert consultation, that’s 600 million hours! Even with every contractor in the country working overtime, that’s an impossible number.

But, could this work be done without the input of contractors and other experts? Probably not. At least some expert input is necessary most of the time because, as Grant said during our interview, “There’s no cookie cutter theme. Everyone needs to do discovery work.”

When you consider the position this puts contractors in, you begin to get a sense of the scope of this small piece of the much larger problem. When a homeowner has a project in mind, or they need to do an upgrade immediately (the boiler has stopped working, the water heater isn’t heating, etc.), it’s common to get about three quotes from different contractors. This means each time a contractor gives a quote they have a one in three chance of getting the work. Yet, the cost in both time and actual dollars, of giving estimates is real. Making every home more energy efficient presents a serious lack of skilled labor.

Es Trisidder, certified Passivhaus and AECB Carbonlite Retrofit designer, suggests a do-it-yourself approach to solving the problem. He transformed his home from an average 1970s-built timber frame house into an amazingly efficient, comfortable home himself. “With retrofitting buildings, there’s a tremendous scope for a DIY-led approach where the homeowner does a lot of the work themselves.” However, he adds, “With the complexities of a retrofit, you’d probably want some expert input.”

The Learning Curve

So how would an average person, without much construction or remodeling experience, go about learning what materials they need to do in order to make their home more energy efficient? It feels like an overwhelming task. Marjory van Dillen, advice and sales team member at Groenpand, works as an energy coach.

She visits people’s homes and helps them create a plan for projects that will result in a far more efficient and comfortable home. “Sometimes the plans are standard, some are more creative, but in the end, they have a plan and can work for the next 10 years,” she said, adding, “You don’t have to do everything all at once.”

All of the experts agreed that weatherization is probably the best place to start for most people. Adding insulation where there isn’t any is going to deliver significant results. But, even with a project like adding insulation, expert input is often necessary, because moisture can be an issue depending on your climate.

Plus, “insulation” is a huge category. My first thought is the fluffy, itchy, pink fiberglass insulation, but now there are many other types, like:

Mineral wool

Cellulose

Natural fibers

Polystyrene

Polyisocyanurate

Polyurethane

Perlite

Cementitious foam

Phenolic foam

And that’s not to mention all of the different facings attached to the insulation. Choosing the best product for your situation and the application can be a complex process.

Results Are Sometimes Surprising

Almost any project to improve the efficiency of a house is at least as complicated as choosing the right type of insulation, and there’s the cost/value equation to consider as well. Often, we tend to think about how much money we will save on our monthly utility bills by improving the efficiency of our homes, but there are other considerations, too.

In an excellent episode of The Energy Transition Show (a podcast), Es described discovering that the towels his family uses stay fresh for much longer because they dry so much faster in a properly ventilated house. He also discovered that using a heat exchange system that captures the heat from water going down the drain in the shower has vastly increased the efficiency of his water heater.

Marjory says that her family left one room of their home “cool” and they use it as a pantry. The result? “The beer stays cold,” she laughs. Sometimes the benefits aren’t necessarily reflected in your utility bills!

What’s Ahead?

No one has a crystal ball, but one thing is certain: the planet will continue warming. Another certainty is that homes will continue to need maintenance. Continuing maintenance provides opportunities to improve emissions while also making houses more comfortable and less expensive to heat and cool—and means that contractors will continue to be busy.

Using technology to smooth the process for contractors and homeowners, as Grant’s company does, is one way to speed up the energy transition. Training more people to work as energy coaches as Marjory does is another. Finally, adhering to standards like those developed by the Passive House Institute can help.

This is a fantastic overview of things and something we're very much experiencing here as first-time home buyers who jumped in feet first with a home built in 1885.

We're prioritizing windows over insulation as our first project because the windows are old and appear to be handmade, so you can quite literally reach between the upper and lower windows and drafts are very very much an issue.

In a lake effect snow region, that's a problem. In a house that uses a gas boiler for heating, its even bigger.

While there's likely zero insulation in the walls, it's very old lath and plaster with asbestos tiles on the outside of the home. So it's far better than if it was newer construction with zero insulation most likely.

Next up will either be the massive (and equally old) boiler in the basement or insulation, we haven't decided yet.

Given the boiler is gas and something along the lines of 90+% of the electric here is from green sources (and super cheap compared to national rates), it will likely be the boiler next. Though I have to research everything involved in that switch.