The Grid, Part 3: Measuring Electricity

This issue was supposed to be about permitting, but as I was doing the research, I came across an article from Energy Markets & Policy from the Berkeley Lab with this title and blurb:

Grid connection backlog grows by 30% in 2023, dominated by requests for solar, wind, and energy storage

With grid interconnection reforms underway across the country, a Berkeley-Lab led study shows nearly 2,600 gigawatts of energy and storage capacity in transmission grid interconnection queues

My question after reading that was “Is 2,600 gigawatts a lot? Would it make a difference in the looming electricity demand?” Finding the answers to those questions took me down an entirely different path of research, because before we can talk about interconnection and permitting, we need to understand how much electricity we use now and how much we’re going to need as the world transitions away from fossil fuels.

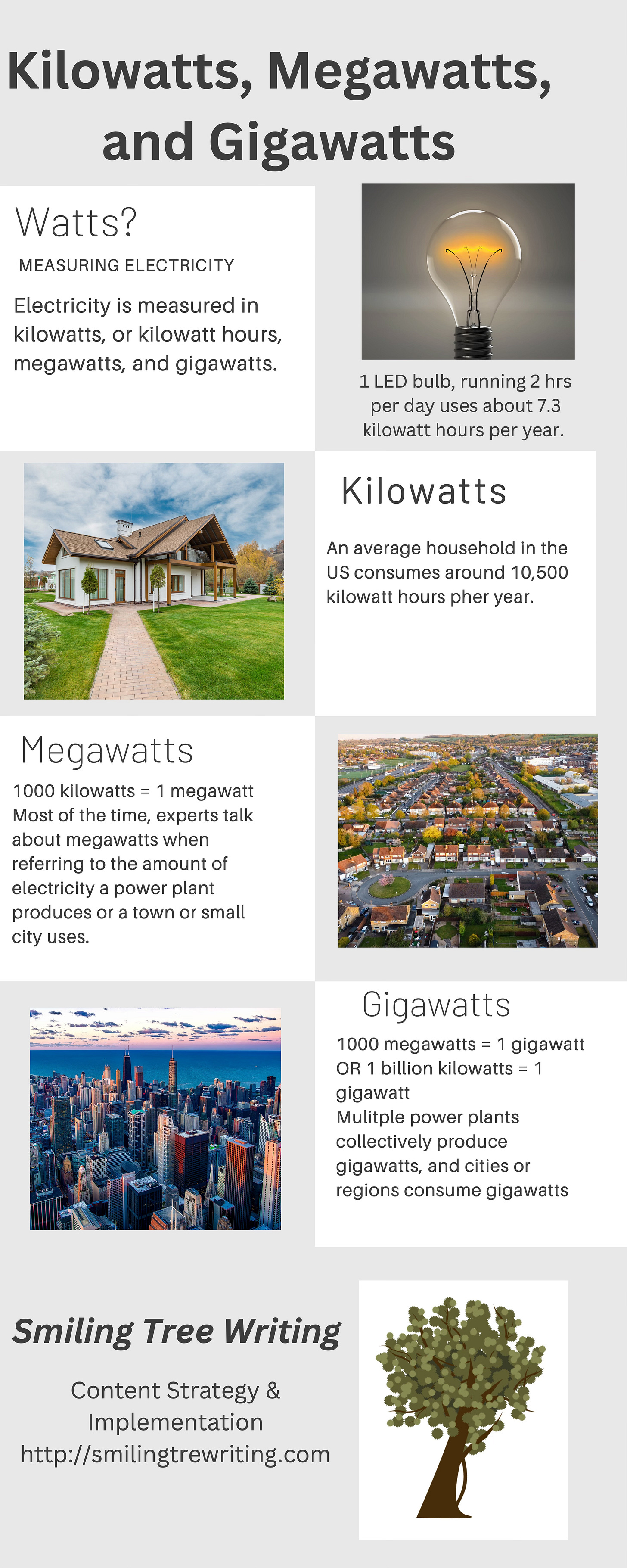

Quick note about definitions:

Watt: one unit of electricity

Kilowatt: 1,000 watts

Megawatt: 1,000 kilowatts

Gigawatt: 1,000 megawatts, or 1 billion watts

The difference between a kilowatt and a kilowatt hour (what you see on your power bill) is a tad confusing. Here’s an explanation I found helpful: “Watt-hours are a combination of how fast the electricity is used (wats) and the length of time it is used (hours). For example, a 15-watt light bulb, which draws 15 watts at any one moment, uses 15-watt hours of electricity in the course of one hour.”

As usual, I started by trying to understand how much electricity it takes to operate an average house, because when a big thing is related directly to my life it’s easier to grasp. I found wildly different answers, ranging from around 6,000 kilowatt hours (kWh) to around 14,000 kWh.

I checked my own utility bill, and found that in July my house used 677.93 kWh. So, rough math says we use around 8,000 kWh per year. My house isn’t average, though, because we don’t have central heat and air. We use an electric space heater to supplement a propane heater in the winter, and a window AC unit in the summer—and we live in an old, uninsulated house— which likely puts our energy use somewhat above average.

Even so, we hit nearly in the middle of the 6,000-14,000 kWh average I found.

But I still didn’t understand what the 2,600 gigawatts in the Berkeley Labs article meant. I mean, on the face of it going from kilowatt to megawatt to gigawatt seems fairly simple, but 2,600 also doesn’t seem like a whole lot, but that’s deceptive. I made a simple infographic to show the differences:

So yes: 2,600 gigawatts is a LOT and would definitely make a big difference as we move away from fossil fuels to electricity. In fact, according to the American Power Association, “As of January 2024, America has nearly 1.3 million megawatts of generation capacity.”

That means we currently have 1300 gigawatts of generating capacity. That means if all of the power generating projects currently ready to connect to the existing grid could be connected tomorrow, power generation would double.

And that brings us back to permitting. The backlog is growing longer, wait times are also getting longer, and the demand for power continues to increase.

Who needs permission for what?

In podcasts, articles, and social media posts and conversations about energy that I encounter, the backlog of interconnection requests comes up frequently. The topic might be a big transmission line that connects regions, solar arrays on warehouses to generate power for an electric fleet, or even rooftop solar panels and battery storage for homeowners in the case of storms. The thing they all share is a need for permits from various authorities.

I emailed my local utility company to ask for an interview for this issue and received a reply explaining that “utility infrastructure investments are not overseen by state or local permitting agencies in Tennessee.” Instead, they are “likely regulated by a combination of city and county laws related to business and residential development.”

It’s not a very clear answer, and is also indicative of the problem as a whole. Connecting to the electrical grid as a power generator is difficult for pretty much everyone except the big generators who typically use fossil fuels.

And, all of this brings us back around to why there’s a backlog of interconnection permit requests? What’s the holdup? What can be done about it? What is being done? Hopefully, I’ll answer those questions in the next issue—unless I end up running down other paths of inquiry again!

Request: If you enjoy this newsletter and find it helpful, please consider sharing it with a friend or two. I’d love to see the community grow, as we all tackle the thorny problem of climate change together. The content is free, and as of now I plan for it to remain free.