Buildings: Resiliency

Merriam-Webster offers two definitions for resiliency:

The ability of something to return to its original size and shape after being compressed or deformed.

An ability to recover from or adjust easily to adversity or change

In the last few years, I’ve written quite a bit about resiliency in computer systems—things like how quickly a system can recover following a cyber attack, or natural disaster, or other unforeseen event that takes a system down. But, more recently, I’ve been learning about a different sort of resiliency: recovery following a climate event.

If you’ve ever watched news coverage of a tornado, hurricane, flooding, wildfire, or other big weather event, you know what resiliency is all about—and you probably know that we need our buildings to be more resilient, our communities to be more prepared, and we need to have personal safety plans. But what does all of that mean, exactly? What should our expectations be for our specific locations?

It doesn’t make sense for people in the plains states to abide by seismic codes, but if you live in an area like San Francisco, it’s important for building codes to include regulations to protect people. Similarly, if you live in South Florida, you benefit from the strong building codes adopted in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

One thing that is certain when it comes to climate change: the planet is warming and will continue to warm for some time. A recent study from Stanford found that we are likely to surpass 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by the 2030s no matter what happens between now and then. In other words, even if we stopped producing greenhouse gasses entirely today, the global temperature would continue to rise.

As that happens, the weather will become more volatile—warmer, wetter, and stormier.

Even if you happen to think that climate change is a hoax or you think that it’s not caused by human activity, the fact remains that storms are happening with increasing frequency, and the weather is behaving in unpredictable ways. We must adapt in order to protect ourselves, loved ones, and communities.

Like everything involving climate change, resilience is a multi-faceted issue with many different considerations. For example, is your local water utility ready for flooding? Will you have potable drinking water in the event of a weather event? This series is about buildings, but resiliency is a huge topic and buildings are connected to electrical systems, water systems, and they make up neighborhoods and communities.

Although some areas are more prone to certain weather events than others, climate changes means you may need to consider things you didn’t need to in the past. For example, in the southeast, where I live, we are more vulnerable to tornadoes and wildfires than in the past. Most of the world is more likely to experience flooding, and of course, record-breaking heat waves are going to continue everywhere.

Heat

The last issue of this newsletter was all about materials for retrofitting homes to be more energy efficient. Most of those same kinds of projects, like adding insulation, electrifying everything, and getting expert input, can help protect your home during extreme heat.

Insulation keeps the cool air in and the hot air out during the summer just as it keeps the warm air in and cold air out during winter. Blocking sunlight with awnings, black-out curtains, or even window tinting is another good way to lower the temperature inside your house. Energy.gov offers some good tips on selecting window attachments, and suggests looking for products certified with the Attachments Energy Rating Council (AERC).

When you need to replace your roof, you may want to consider a cool roof and use either materials or a coating to reflect sunlight and help keep your home cool. You might also consider having your roof inspected regularly even if you aren’t ready to replace it, because heat can cause shingles to contract and expand.

Flooding

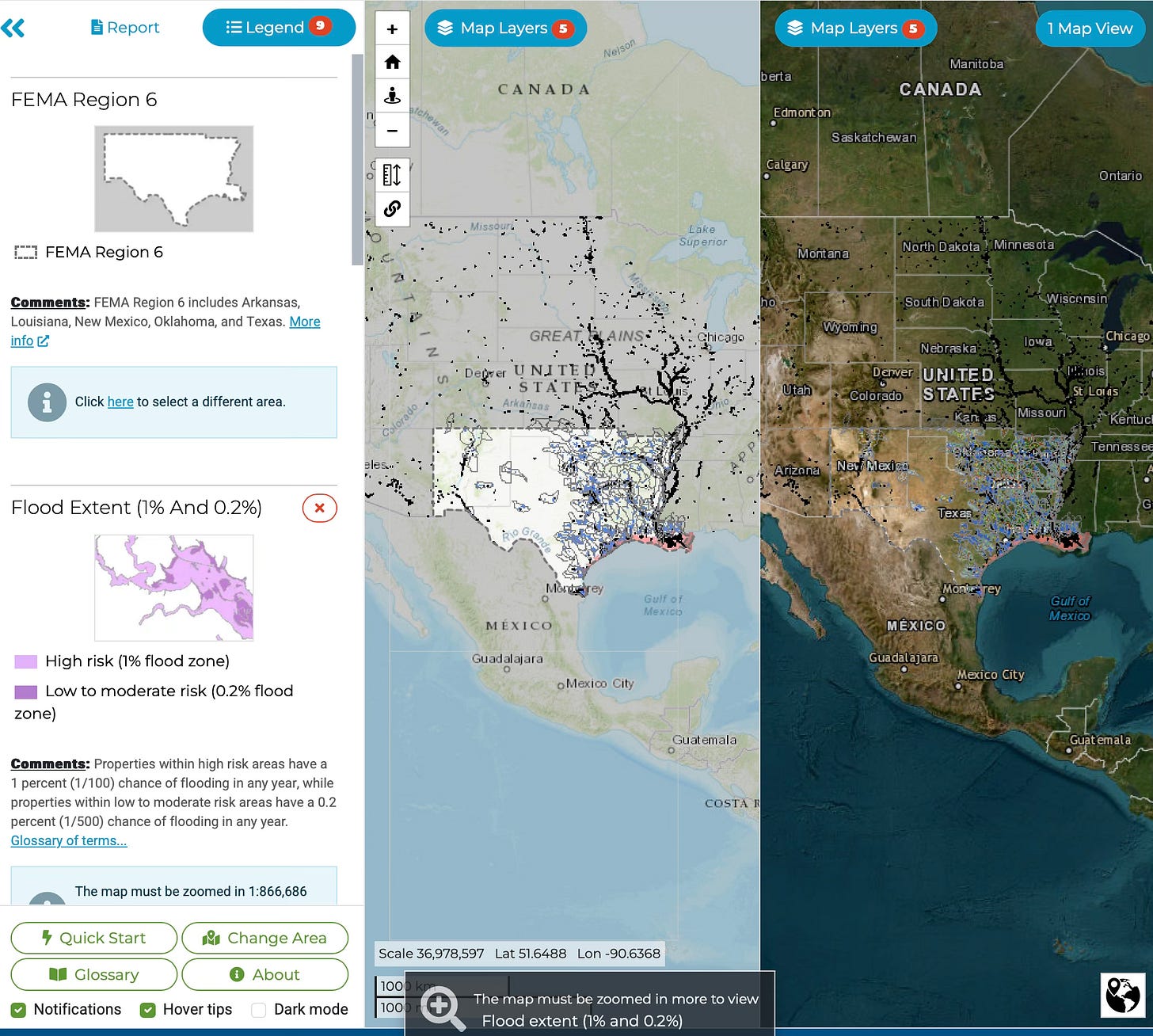

Floods and droughts are the two big weather risks that are going to affect the most people around the world. One of the most important things to know about protecting buildings during floods is the Base Flood Elevation (BFE) of your home. According to FEMA, the BFE is how high the water is expected to rise during flooding.

BFE is used in determining insurance coverage, so there’s a good chance you know if you live in a flood prone area. But, this article is about how the weather is becoming less predictable, so it’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with flood protection even if you don’t live in a flood plain. Here are a few tips from FEMA:

Replace carpeting with tile

Flood-proof your basement if you have one

Use flood-resistant insulation and drywall (one more thing to consider when retrofitting!)

Keep an updated list of your belongings

Store valuables in waterproof containers, on the upper floors of your home

Secure anything outside that could be swept away, such as patio furniture or garden decor

Seal cracks or gaps around your windows, where pipes enter your home, etc.

Make sure your drainage system directs water away from your home

Add water-resistent sheathing to your exterior walls to prevent shallow flooding

Wildfire

Fires are becoming more common in places where they’ve previously been uncommon, and are happening at unexpected times. As I’m typing this, five wildfires are burning in Texas, with the Smokehouse Creek Fire having buried over one million acres. Last August, the deadliest wildfire in a century burned a large portion of Maui.

In the western United States where fires are more common, wildfire season was extended from five months to seven in the 1970s, and the average length of time fires burn has increased from six days to 52 days. The increases in the number of fires and their intensity is due to interconnected factors: drought, less snow, rising temperatures, and less rain in the summer. Experts predict that fires will continue to become more frequent, larger, and more intense as temperatures continue to rise.

You can create defensible space zones around your house:

Zone 0: from your house to five feet away

Zone 1: 5-30 feet

Zone 2: to your property line or 100 feet away

Zone 3: adjacent to roads and driveways, 14 feet overhead, and 10 feet from the edge of the road

Zone 4: area shared with neighbors or others

Zone 0 is sometimes called the “ember resistant” zone, and it’s important to keep it as clear of combustible material as possible. The “miracle house” in Lahaina is a good example of how important this zone can be. The house is the only one on an entire block that survived the Maui fire, and it’s likely because the owners installed river rock, extending from the exterior walls of the house about five feet out.

In Zone 1, you want to make sure there’s plenty of space between trees and shrubs, no smaller trees or shrubs are growing under taller ones, and diligently remove dead vegetation or debris. Irrigating Zone 1 is also helpful. Firewise USA offers some additional tips for fire prevention, as well as a list for surviving a fire if you get trapped.

Hurricanes

As the oceans get warmer, hurricanes get stronger and slower. That increases the amount of damage they do to buildings. Along with the more powerful winds, the more severe hurricanes bring worse storm surges, which cause flooding. The tiny bit of good news here is that some models predict either no change or a slight decrease in the number of hurricanes that happen each year.

Protecting buildings during hurricane season is similar to protecting them from flooding, but with some additions, such as boarding up windows to keep them from breaking in the high winds.

Tornadoes

Scientists understand the link between rising global temperatures and events like droughts, floods, hurricanes, and fires, but it’s less obvious exactly how tornadoes and climate change are connected. The United States experiences more tornadoes each year than any other country, with about 1200 per season, but we still don’t have great records about them, and models don’t replicate them especially well. However, there are still some indications that climate change will bring about more tornadoes.

Warmer air provides energy for storms to develop and to become more intense, and it holds more moisture than cooler air—in other words, warmer air has all of the ingredients for tornadoes. Another factor is atmospheric instability, when the warm air closer to the surface of the earth clashes with the cooler air above it.

“Tornado season” has generally been from March until May, and then October and November, which are times of the year when the air is warm, wet, and unstable. As winters become milder, the conditions that are favorable for tornadoes are likely to occur for longer periods of time and in places that aren’t usually warm enough for them.

A study published in the Journal of the American Meteorological Association predicts, “Supercells are projected to become more numerous in regions of the eastern United States, while decreasing in frequency in portions of the Great Plains. Supercell risk is expected to escalate outside of the traditional severe storm season, with supercells and their perils likely to increase in late winter and early spring months.”

Although things like impact resistant garage doors are available, and you can invest in an at-home storm shelter, the most important thing to protect during a tornado is yourself. No building is completely safe, but some communities have shelters. It’s helpful to know if there’s a shelter near you.

If you can’t get to a shelter, go to a basement, or the innermost room on the lowest floor of your home, stay away from windows, get under something heavy, like a table or workbench, cover your body with a blanket or mattress, and protect your head.